By Prathik Desai

Compiled by: Vernacular Blockchain

In the late 1980s, Nathan Most was working on the U.S. stock exchange. He was not a banker or a trader, but a physicist who had worked in the logistics industry, shipping metals and commodities. His starting point was not financial instruments, but actual system design.

At the time, mutual funds were a popular way to get broad market exposure. They offered investors the opportunity to diversify, but there was a delay. You couldn’t buy or sell in real time during the trading day, you had to wait until the market closed to find out the transaction price (this is still the case with mutual funds today, by the way). The experience seemed outdated, especially for investors who were used to buying and selling individual stocks in real time.

Nason proposed a solution: create a product that tracks the S&P 500 but trades like a single stock. Package the entire index into a new form and list it on a trading platform. The proposal was met with skepticism. Mutual funds were not designed to be traded like stocks, the legal framework did not exist, and the market did not seem to have the demand.

Still, he pushed forward.

In 1993, the S&P Depositary Receipt (SPDR) debuted under the ticker SPY. It was essentially the first exchange-traded fund (ETF). An instrument that represented hundreds of stocks. What was initially seen as a niche product grew to become one of the most traded securities in the world. On many trading days, SPY traded more than the stocks it tracked. A synthetic financial instrument turned out to be more liquid than its underlying asset.

Today, this story is once again relevant, not because of the launch of yet another fund, but because of what is happening on the chain.

Investment platforms like Robinhood, Backed Finance, Dinari, and Republic are beginning to offer tokenized shares — blockchain-based assets designed to mirror the prices of private companies like Tesla, Nvidia, and even OpenAI.

These tokens are promoted as a way to get price exposure, not ownership. You don’t have shareholder status, and you don’t have voting rights. You’re not buying equity in the traditional sense, but a token that’s tied to it.

This distinction is important because it has sparked some controversy.

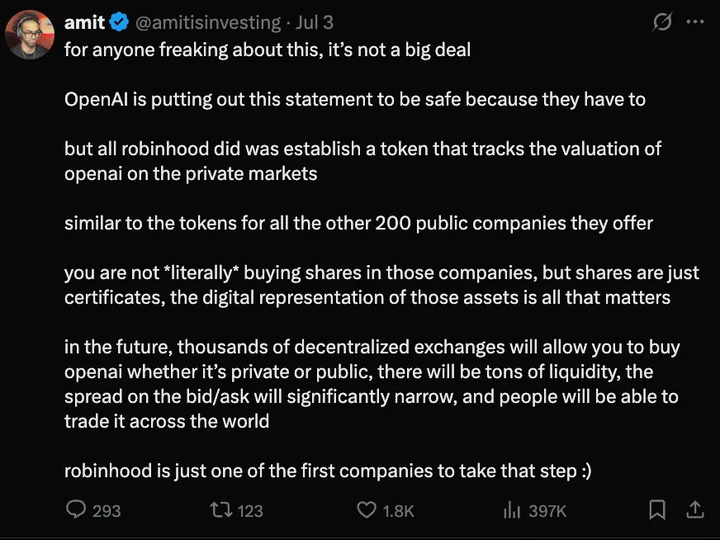

OpenAI and even Elon Musk have expressed concerns about the tokenized stocks offered by Robinhood.

@OpenAINewsroom

Robinhood CEO Tenev later clarified that these tokens actually provide retail investors with exposure to these private assets.

Unlike traditional stocks issued by the company itself, these tokens are created by third parties. Some claim to hold real stocks as 1:1 endorsement, while others are completely synthetic. The experience is familiar: the price movement is like stocks, and the interface is similar to broker applications, but the legal and financial substance behind it is often weak.

Still, they’re attractive to some investors, especially those outside the U.S. who don’t have easy access to the U.S. stock market. If you live in Lagos, Manila, or Mumbai, investing in Nvidia typically requires an overseas brokerage account, high minimum balances, and lengthy settlement cycles. Tokenized shares eliminate these frictions by trading on-chain, tracking the movements of the underlying stock on the exchange. No wires, no forms, no gatekeepers, just a wallet and a marketplace.

This convenience may seem novel, but its mechanics are reminiscent of something much earlier.

But there’s a practical problem here. Many platforms — like Robinhood, Kraken, and Dinari — don’t operate widely in emerging economies outside the U.S. It’s unclear whether an Indian user, for example, can legally or practically buy tokenized shares through these avenues.

If tokenized stocks really want to expand access to global markets, the friction will come not only from technology, but also from regulation, geography, and infrastructure.

How Derivatives Work

Futures contracts have long offered a way to trade on expectations without having to touch the underlying asset. Options let investors express a view on volatility, timing or direction, often without having to buy the stock itself. These products have become alternative ways to access the underlying asset.

Tokenized stocks have emerged with similar intentions. They do not claim to be better than the stock market, but simply provide another way for those who have long been excluded from public investments to enter.

New derivatives often follow a recognizable trajectory.

Initially, the market is full of confusion. Investors don't know how to price, traders are hesitant about the risk, and regulators remain on the sidelines. Then, speculators enter. They test boundaries, expand products, and arbitrage inefficiencies. Over time, if the product proves useful, mainstream players gradually adopt it. Eventually, it becomes infrastructure.

This is true for index futures, ETFs, and even Bitcoin derivatives on CME and Binance. They were not originally tools for the masses, but rather playgrounds for speculators: faster, riskier, but more flexible.

Tokenized stocks may follow the same path. Initially used by retail traders to chase exposure to hard-to-reach assets such as OpenAI or pre-IPO companies. Then used by arbitrageurs to exploit the price difference between tokens and underlying stocks. If trading volumes continue and the infrastructure matures, institutional trading desks may also start using it, especially in regions where compliance frameworks emerge.

Early activity can appear noisy: low liquidity, wide spreads, weekend price swings. But that’s how derivatives markets often start. They’re not perfect replicas, they’re stress tests. They’re how the market discovers demand before the asset itself adjusts.

This structure has an interesting feature, or flaw, depending on your perspective.

Time difference.

Traditional stock markets have opening and closing hours. Even derivatives based on stocks are mostly traded during market hours. But tokenized stocks don’t necessarily follow these rhythms. If a US stock closes at $130 on Friday, and a major event happens on Saturday — like an earnings leak or a geopolitical event — the token may react to the news immediately, even though the underlying stock itself is static.

This allows investors and traders to digest the impact of news flow while stock markets are closed.

The time lag only becomes a problem when the trading volume of tokenized stocks significantly exceeds that of the stocks themselves.

Futures markets address such challenges through funding rates and margin adjustments. ETFs rely on authorized participants and arbitrage mechanisms to keep prices consistent. Tokenized stocks, at least for now, do not have these mechanisms in place. Prices may deviate, liquidity may be insufficient, and the connection between the token and its reference asset relies on trust in the issuer.

However, this level of trust varies. When Robinhood launched tokenized shares of OpenAI and SpaceX in the EU, both companies denied involvement, coordination or formal relationship.

This is not to say that tokenized stocks are inherently problematic. But it is worth asking, what are you buying? Is it price exposure, or a synthetic derivative with unclear rights and recourse?

@amitisinvesting

The underlying infrastructure of these products varies widely. Some are issued under European frameworks, while others rely on smart contracts and offshore custodians. Platforms like Dinari are trying a more compliant path. Most are still testing the boundaries of legal possibility.

In the United States, securities regulators have yet to make a clear statement. The SEC has a clear stance on token sales and digital assets, but tokenizing traditional stocks is still a gray area. Platforms remain cautious. For example, Robinhood chose to launch its product in the European Union rather than in the United States.

Even so, the need is clear.

Republic already provides synthetic exposure to private companies like SpaceX. Backed Finance is packaging public stocks and issuing them on Solana. These efforts are early, but they persist, and the underlying model is about solving friction, not finance. Tokenized stocks may not improve the economics of ownership, because that’s not their goal. They’re just simplifying the experience of participation. Maybe.

For retail investors, participation is often the most important thing.

Tokenized stocks don’t compete with stocks, they compete with the effort to acquire them. If investors can get directional exposure to Nvidia in a few clicks, in an app that also holds stablecoins, they may not care that the product is synthetic.

This preference is not new. SPY proved that packaging can become a major market. The same is true for derivatives such as CFDs, futures, options, etc., which started as tools for traders and eventually served a wider audience.

These derivatives sometimes even lead the underlying assets, absorbing market sentiment and reflecting fear or greed faster than the underlying market.

Tokenized stocks may follow a similar path.

The infrastructure is immature, liquidity is spotty, and regulation is unclear. But the underlying impulse is recognizable: build an instrument that reflects the asset, is accessible enough, and is interesting enough for people to participate. If this representation can remain stable, more trading volume will flow to it. Eventually, it will no longer be a shadow, but a signal.

Nathan Most didn’t set out to reinvent the stock market. He saw inefficiencies and looked for smoother interfaces. Token issuers today are doing the same thing. Only this time, the wrapper is a smart contract, not a fund structure.

It will be interesting to see whether these new packaging can hold their own in a volatile market.

They are not stocks, nor are they regulated products. They are instruments of proximity. For many users, especially those who are far from traditional finance or in far-flung regions, that proximity may be enough.