By Felix Ng

Compiled by Aki Chen, Wu Shuo Blockchain

The full text is as follows:

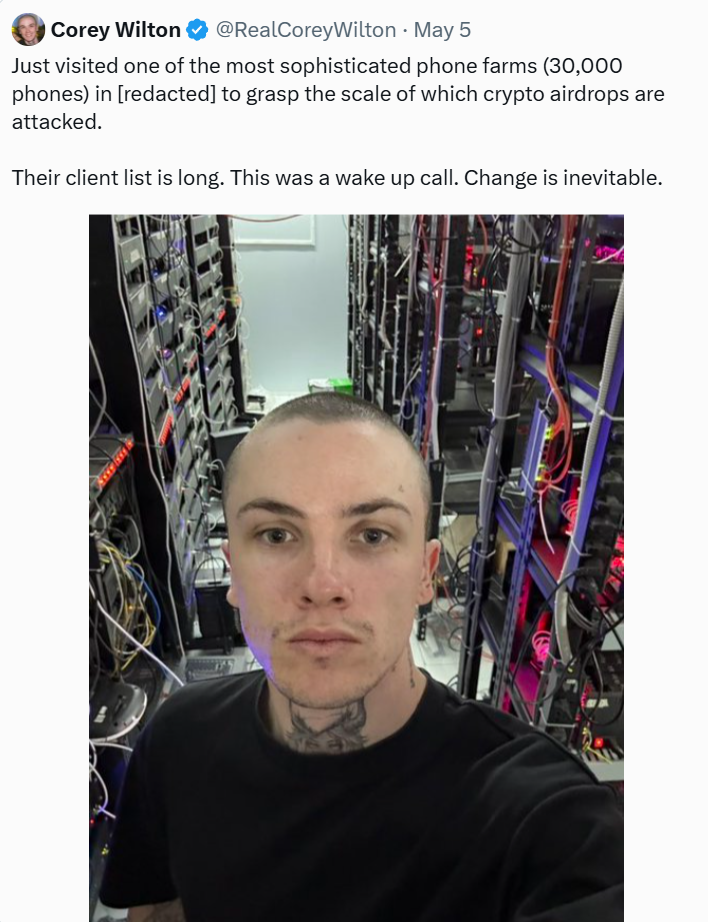

In a refrigerated tin shed just 40 minutes from Ho Chi Minh City, Mirai Labs CEO Corey Wilton first truly grasped the scale of the abuse of crypto airdrops. "It was truly horrifying," Wilton said in an interview. He had just visited a "phone farm" in southern Vietnam, where he estimated at least 30,000 smartphones were stacked in a room the size of a studio apartment.

For the past four years, Wilton has long hoped to witness the kind of behind-the-scenes operations that brought down his flagship NFT horse racing game, Pegaxy, in 2021. "Pegaxy was taking off, and we were peaking at around 500,000 daily active users," Wilton recalls. "That's when we started getting reports of 'bot farms'." These bots could manipulate hundreds of accounts simultaneously, quickly snap up high-probability horses, and repeatedly participate in races to win in-game currency, which could then be cashed out in real life. "You'd see screenshots posted of people with a dozen or two dozen apps running simultaneously, and similar images were popping up all over social media," he explains.

Pegaxy is a horse racing game with 15 horses that is automatically run by the system. Wilton said that bot farms changed the game from "who can win" to "who can extract value the fastest"—a shift in the game's dynamic and accelerated the project's decline.

On-site visit: Unveiling Vietnam's "professional-grade" mobile phone farm

In May of this year, Wilton finally got his wish and was given an exclusive tour of a “highly specialized phone farm” in Vietnam, thanks to a former Pegaxy player who had stumbled upon the farm on TikTok.

“I went to two places, both about 40 minutes’ drive from where I was, in relatively remote areas,” he recalled. “No foreigners would ever go there, and they didn’t want anyone to know about it.” Wilton described one of the locations as a tin shed right next to the street, with the air conditioning turned up to “as cold as it could get.”

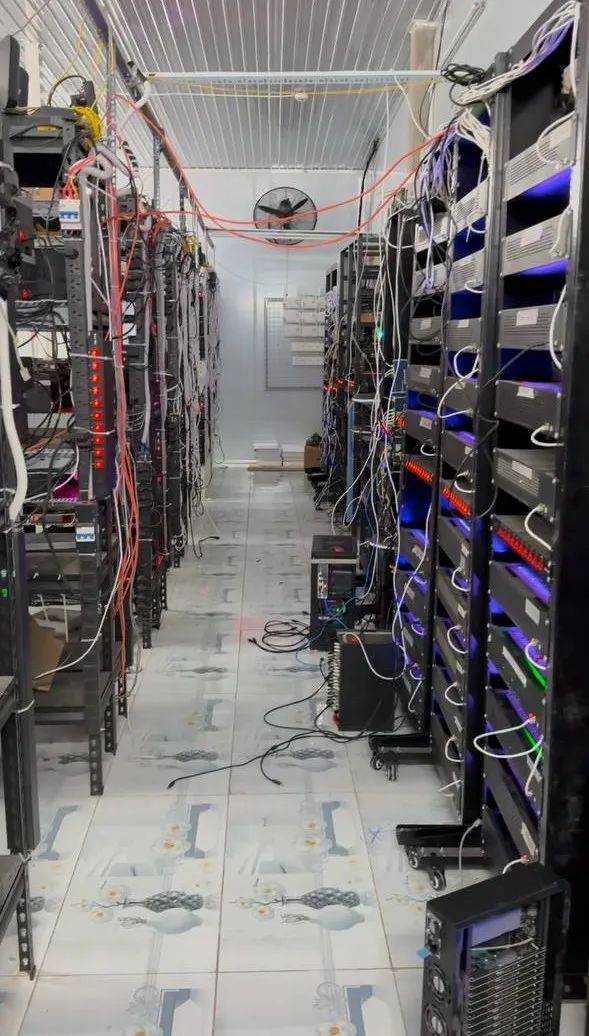

Inside the shed, metal racks are stacked densely with thousands of smartphones, leaving only narrow passages for employees to pass through. The entire layout resembles a knockoff crypto mining farm.

Wilton explained that the company demonstrated the "leasing" aspect of the business, allowing customers to rent the mobile phone farm for any purpose. Unlike traditional robot servers, each device in a mobile phone farm is equipped with a unique SIM card and device fingerprint. It can also disguise its IP address and location, making it more difficult to detect. This makes it particularly suitable for systems that require each account to be linked to a mobile phone number. Furthermore, mobile phones offer a high cost-performance ratio between computing power and cost, and even if a device is damaged, it can be quickly replaced without significantly impacting overall operations.

Wilton explained that in cases he witnessed, an operator controlled a "master phone" via a computer, which in turn connected to over 500 "slave phones." Any action performed on the master phone was replicated on all the slave devices. "Their clients are mostly from the Web2 industry. For example, K-pop agencies rent these devices to boost traffic, while casinos use them to simulate real players, making the game appear more 'real,' but they're actually designed to suppress you and trick you into losing money."

"Some Web2 players also play mobile games in bulk, raising accounts and then selling these upgraded accounts," he added. However, Wilton said the farm's core business is actually "manufacturing."

This operator buys damaged or obsolete smartphones at low prices, then modifies them using software and other means, ultimately packaging them into "self-service phone farms" and selling them overseas. The project produces over 1,000 ready-to-deploy farm phones per week, with each "phone farm kit" containing approximately 20 devices. Wilton explained that these individuals don't operate the phones themselves. They don't collect airdrops or perform any other operations themselves. Their primary business is to package and sell these devices to people overseas who want to operate them from home. "Then all you have to do is keep them online and buy more phones to connect them," he explained.

Wilton lamented that it's no wonder that "bot-assisted crypto airdrop scams" have become a persistent problem in the crypto industry. Crypto airdrop scams involve creating a large number of wallet addresses and spoofing user behavior to obtain free tokens intended for genuine early adopters. While most crypto airdrops don't require phone number verification, unique device fingerprints and IP addresses can still be used to circumvent anti-Sybil protection mechanisms.

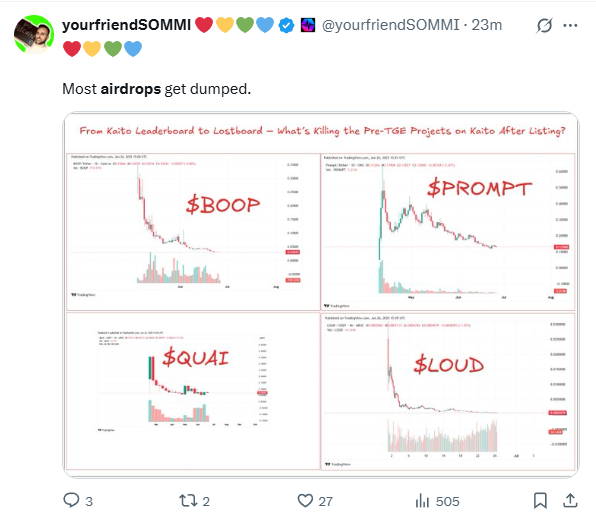

This type of "airdrop" scam often leads to users immediately selling their tokens after receiving them, impacting market prices and making it more difficult for real users to access the airdrop. Many projects experience significant false activity before an airdrop, but once the airdrop is complete, user numbers and token prices often plummet.

Crypto airdrops are controversial, with bots widely blamed for their actions.

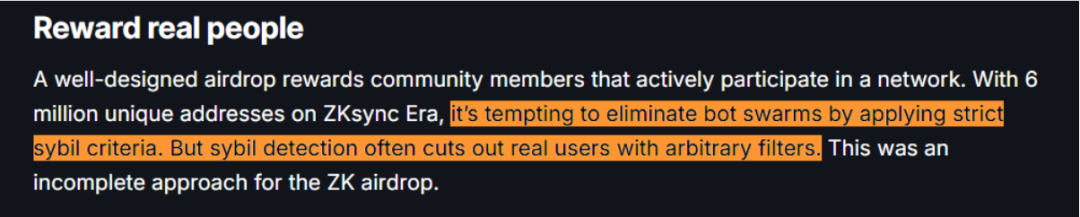

Whether controlled by a large number of mobile phones or a single computer, bot activity has wreaked havoc on crypto airdrops. Last June, ZKsync, an Ethereum zero-knowledge (ZK) Layer 2 scaling project, faced widespread criticism after its airdrop was targeted by a large number of bots. Users accused it of facilitating the exploitation of "bots."

On-chain data analysis platform Lookonchain announced that an "airdrop hunter" had claimed over 3 million ZKsync (ZK) tokens across 85 wallet addresses, with a total value of $753,000 at the time. Another user boasted on social media that they had profited nearly $800,000 through an "extremely efficient $ZK Sybil attack strategy."

A "Sybil attack" is a security threat in which an attacker creates multiple false identities in an attempt to gain an unfair advantage in a network system. The term originates from the book "Sybil," which describes the case of a woman with multiple personality disorder. Mudit Gupta, head of security at ZKsync competitor Polygon, called it "perhaps the most exploitable and over-exploited airdrop in history," attributing the problem to a lack of anti-bot mechanisms. This is despite ZKsync setting seven eligibility criteria to prevent Sybil attacks.

ZKsync responded in its official FAQ that current Sybil attack strategies are becoming increasingly complex and difficult to distinguish from real users; and if overly strict screening criteria are adopted, although some Sybil attackers can be blocked, a large number of real users may be accidentally harmed.

However, just last month, Binance offered a different perspective when cracking down on bot activity within its "Binance Alpha Points" program. "Traditional bots typically follow predictable, repetitive patterns of behavior, making them relatively easy to identify," a Binance spokesperson said in an interview. "But with the rise of AI-powered bots, we're now dealing with a system that more closely resembles human behavior—from browsing habits to interaction duration, it can closely mimic a real person, making identification significantly more difficult." Binance stated that the platform is continuously increasing its anti-bot efforts and developing new tools to identify anomalous operations from large-scale behavioral patterns. For example, address-entity correlation analysis can help identify clusters of wallets controlled by the same actor, even if these wallets appear to be independent.

These analyses are particularly crucial for uncovering manipulations such as disguised holdings, multisend manipulation, and wash trading—tactics commonly used by AI-powered bots to fake real participation and liquidity. Crypto airdrops aren't the only ones suffering; bots have also been accused of flooding the market with worthless meme coins. Coinbase Product Manager Conor Grogan recently posted on the X platform, stating, "The vast majority of tokens currently listed on the PumpFun and LetsBonk platforms are controlled by bots." He found that on the meme coin platform LetsBonk, top accounts were releasing a new token every three minutes on average.

Daren Matsuoka, a data scientist and partner at a16z Crypto, believes that Sybil attacks are a relatively recent problem. "For most of the history of cryptocurrency, we've had some inherent resistance to Sybil attacks because gas fees have always been high on these Layer 1 blockchains," he said in an April episode of the a16z Crypto podcast.

“In the past, you had to pay a few or even tens of dollars in transaction costs to obtain airdrop qualifications. But with the continuous optimization of infrastructure, the cost of operation has become very low. I believe this will completely change the game landscape of attack and defense mechanisms.” Eddy Lazzarin, Chief Technology Officer of a16z Crypto, has been emphasizing the importance of building a “proof of human” mechanism.

"AI can now generate massive amounts of realistic behavioral records. The most advanced bot farms are now nearly impossible to reliably identify, and even moderately skilled farms will soon be equally difficult to detect," Lazzarin wrote in an article in May of this year. Lazzarin is most interested in building a "proof of personhood" mechanism: one that allows real humans to easily and freely verify their identities, while making it costly and difficult for bots or fraudsters to commit fraud on a large scale. He cites Sam Altman's iris scanning project, World, as a prime example of this type of mechanism. The core concept of the project is that each person can only register for a World ID once, and its uniqueness is verified through an iris scan (because everyone's iris is unique).

“I’d love to see more people experiment with systems like World ID, which combines biometrics with privacy protections to limit people to just one identity,” Lazzarin added in the airdrop podcast.

However, Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin believes that "one person, one ID" isn't a perfect solution, as it means all past actions could be tied to a single attack point—the key associated with that identity. Once leaked, the risk is enormous. He also points out that biometric and government identification information itself can be forged.

Why not just cancel the crypto airdrop?

If crypto airdrops are so easily manipulated, the most straightforward option seems to be to simply cancel the airdrop mechanism. However, there are also views that airdrops still have their significance. Airdropping tokens to users who actually participate in the protocol not only helps to decentralize project governance, but also disperses control by granting voting rights and other means. In addition, airdrops often create a lot of hot topics. "One obvious reason is: when you distribute a large number of tokens that may have value, it will attract a lot of attention, which in itself has a marketing effect." Lazzarin said. "Airdrops are essentially a marketing tool."

Wilton agreed, noting that projects should assume that some users will sell their tokens, which is essentially the marketing cost of acquiring users. The key is to ensure these users are real people and "willing to stay for the long term." Meanwhile, Binance believes that automated bots are not inherently harmful. In fact, in certain scenarios, if used appropriately and transparently, bots can actually play a positive role—for example, providing liquidity, executing strategies on behalf of users, or conducting stress testing simulations during audits.