Wall Street billionaires are not used to being excluded from decision-making.

But they found themselves in an awkward position after U.S. President Donald Trump ignored their calls to cancel tariffs, which the financial tycoons fear could jeopardize the U.S. economy.

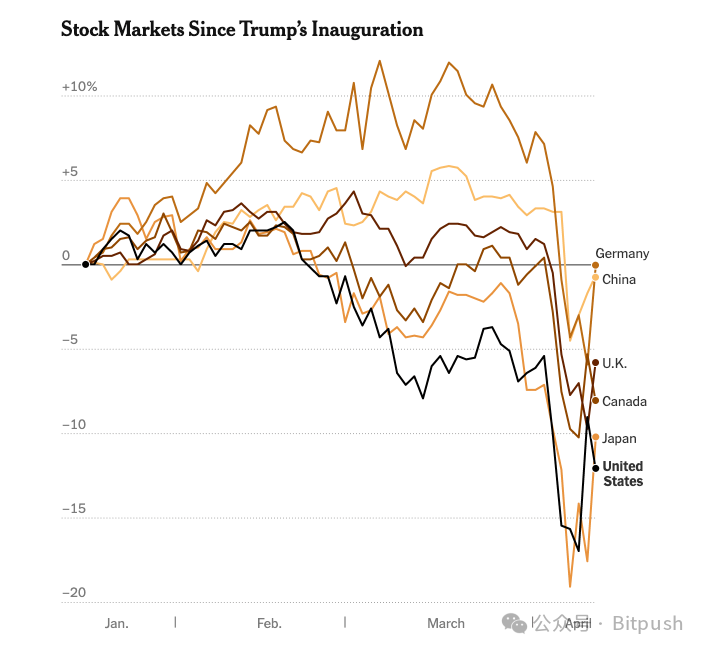

As losses in the U.S. stock market rapidly mount, corporate titans have tried everything — phone calls, social media posts, even a sobering shareholder letter — to try to change Trump’s mind.

Just a day after Trump announced the latest round of sweeping tariffs, several big bank CEOs, including JPMorgan Chase's Jamie Dimon, held private meetings with Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick arranged through a Washington lobbying group.

But Lutnick was not persuaded to change his stance, according to three people familiar with the matter.

Over the weekend, Trump’s top donors tried another tactic, calling White House Chief of Staff Susie Wiles and Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent. Those efforts also came to nothing, according to people familiar with the matter.

By Monday, hedge fund billionaires — many of whom had been high-profile supporters of a second-term Trump — were beginning to express their displeasure publicly.

"The global economy is sliding down because of bad math," hedge fund manager William A. Ackman wrote on X on Monday morning. "The president's advisers need to admit their mistakes by April 9 and correct course before they make a big mistake."

Others have joined in, calling for a more forceful rebuttal.

Andrew Hall, a billionaire oil trader who has criticized Trump, praised Ackman on Instagram for speaking out: "At least he was willing to change his stance and call out this stupidity. Where are the other 'financial giants'? Why aren't they speaking up?"

A few are indeed speaking out, albeit in more subtle ways. JPMorgan Chase CEO Dimon addressed the issue in a letter to investors Monday morning, saying tariffs could dampen consumer and investor confidence and hamper economic growth. Dimon, who had been positive about tariffs in the days after Trump's election, stopped short of warning of a severe recession but said the unrest "has caused many people to start considering the possibility of a recession more likely."

Laurence D. Fink, chairman of investment giant BlackRock, was more direct at a luncheon at the Economic Club of New York on Monday, warning that "the economy is weakening before our eyes."

In his first public comments on tariffs, Fink also predicted that consumers will feel the pain, citing Barbie dolls as an example of possible price increases. "Most CEOs I talk to would say we are probably already in a recession right now," he told attendees.

The situation has alarmed financiers who once had the ability to influence the decisions of two presidents. It is particularly troubling that during Trump's first term, he often used the rise of the U.S. stock market as a measure of success. "I'm not sure Wall Street can change the president's mind," said Robert Wolf, former chairman of UBS Americas, "but hopefully his donors and friends at Mar-a-Lago will speak out about this wrong approach."

For a brief moment Monday morning, Wall Street seemed to have won over Trump. A report that he planned to suspend tariffs sent stocks gyrating from a decline to a gain. But after the White House denied the report and Trump reiterated his commitment to tariffs, the S&P 500 ended the day down another 0.2%. The index closed Monday nearly 18% below its mid-February peak, on the brink of a bear market.

Source: The New York Times, data as of 4:20 PM EST on April 10

"The Trump Administration remains in regular communication with business leaders, industry groups, and everyday Americans, especially on major policy decisions like reciprocal tariff actions," White House spokesman Kush Desai said in a statement. "But the only special interests guiding President Trump's decision-making are the best interests of the American people -- like addressing the problems caused by chronic trade deficits."

The sell-off has spooked Wall Street, where stable markets generally mean businesses can continue to trade and banks can lend to companies and consumers without fear of default. As stocks fall at a pace not seen since the early days of Covid, Wall Street executives have been scrutinizing their clients and investments for early signs of a possible crisis.

A major investment bank is examining whether it needs to write down the value of billions of dollars in loans it has made to so-called investment-grade companies, generally considered safe investments, ahead of its earnings reports, which are set to begin on Friday, according to a person familiar with the matter.

Another hot topic is the private lending market, which has ballooned since the last major financial crisis in 2008 and often involves financing riskier companies. Private lenders have long believed any stress on their systems would be contained, but the companies have never faced a contraction of this magnitude.

While the concerns of Wall Street bosses often seem unrelated to topics of concern to ordinary people, financial executives have made arguments to Trump that his trade policies threaten not only the stock market but also the U.S. economy.

The 2008 global financial crisis was triggered by a fall in the value of a complex set of mortgage bonds, which ultimately led to a housing market crash that lasted for years. Many U.S. companies rely on sales to countries that have threatened retaliatory tariffs.

When financiers spoke to Trump administration officials in recent days, the response was that the White House is focused on reshoring jobs in industries such as manufacturing that have moved overseas. Trump administration officials said the market turmoil could be a temporary disruption needed to achieve long-term change.

One prominent executive who serves as a middleman between Wall Street and Trump administration officials said he has begun telling colleagues and competitors to stop trying to convince Trump to delay tariffs and instead demand tariff cuts on a case-by-case basis for industries that have trouble quickly replacing imported goods.

There are already signs that Wall Street is already feeling the heat. When some CEOs who met with Lutnick last week reconvened on a call three days later, the discussion focused not on persuading Trump but on how to protect their banks from the impact of his decisions, according to two people familiar with the matter.

By Tuesday morning, even Ackman had tempered his criticism, writing in another X post that he supported Trump's plan to use tariffs to eliminate "unfair trade practices." "But doing so without giving time to reach an agreement would cause unnecessary harm," Ackman added.

Note: This article is compiled from the New York Times and does not represent the position of this platform.