By Joel John and Shlok Khemani

Compiled by: Felix, PANews

I have been camping on a hilltop in the southern Indian state of Kerala for the past week. It’s a strange place to escape Trump’s tariff tactics, since Kerala has always been good at building global connections. Thousands of years ago, the state exported pepper all over the world. According to historian William Darymple, a peppercorn from here was found in the mummified remains of an Egyptian pharaoh thousands of years ago. But what does this have to do with today’s article?

It highlights how networks work in the context of trade. A thousand years ago, ports here facilitated the transport of gold and spices. In turn, they became nodes for the flow of capital. Similar stories played out in London, New York, Calcutta, Hong Kong, and many other trading centers. It's just that some countries have done a better job than others of integrating themselves into the fabric of global trade.

A similar situation is happening in the crypto VC space. As an asset class, venture capital follows an extreme power law. But because we are always chasing the latest narrative, we haven’t studied the extent to which this is happening. In the past few weeks, we created an internal tool to track the network of all crypto VCs.

As a founder, knowing which VCs frequently co-invest can save time and improve your fundraising strategy. Every deal is a fingerprint. Once you visualize these stories, you can unlock the stories behind them.

In other words, it is possible to track down the nodes responsible for the majority of financing in the crypto space and try to find “ports” in modern trade networks, not unlike the merchants of a thousand years ago.

This would be an interesting experiment for two reasons:

- Currently, it operates a venture capital network that is a bit like a "fight club". The venture capital network covers about 80 funds. In the past year, about 240 funds invested more than $500,000 in the seed round. This means that the network maintains direct contact with one-third of these funds.

- But tracking where the money is actually deployed is difficult. Sending founders updates on every fund would just be a distraction. The tracker is a filtering tool to see which funds have invested, in what sectors, and with whom.

For founders, understanding fund allocation is only the first step, and it is more valuable to understand the performance of these funds and who they typically co-invest with. To understand this, the historical probability of fund investments receiving follow-on investments is calculated, but this probability becomes blurred at later stages (such as Series B financing) because companies often issue tokens instead of traditional equity financing.

The first step is to help founders identify which investors are active in the crypto venture capital space. The next step is to understand which funding sources are actually performing better. Once you have this data, you can explore which funds’ co-investments lead to better results. Of course, this is not rocket science. No one can guarantee a successful Series A just because someone writes a check. Just like no one can guarantee marriage after a first date. But knowing what you’re getting into, whether it’s dating or venture capital, is undoubtedly helpful.

Building a path to success

Some basic logic can be applied to identify the funds with the most follow-on rounds in their portfolios. If a fund has multiple companies that raise money after their seed round, then the fund is likely doing something right. When a company raises money at a higher valuation in a subsequent round, the value of the VC’s investment increases. Therefore, follow-on rounds can be an important indicator of performance.

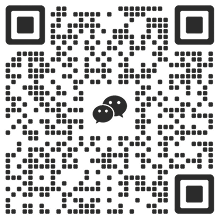

This article selected the 20 funds with the most follow-up financing in their portfolios, and then calculated the total number of companies they invested in during the seed round. Based on this number, the probability of a founder obtaining follow-up financing can be calculated. If a fund invests in 100 companies during the seed round, and 30 of them obtain follow-up financing within two years, the calculated probability of "graduation" is 30%.

It should be noted that the screening criteria set here are for a two-year period. Many times, startups may choose not to raise funds, or raise funds after two years.

Even among the top 20 funds, the power law is extreme. For example, raising money from A16z means you have a 1/3 chance of raising money again within two years. That means one out of every three startups backed by A16z will get a Series A. Considering the odds at the other end are only 1/16, that’s a pretty high graduation rate.

Venture funds ranked near the 20th position (on this list of the top 20 funds that include follow-on investments) have a 7% chance of seeing a company go on to raise money. These numbers look similar, but for ease of understanding, a 1/3 probability is equivalent to the probability of rolling a number less than 3 on a dice, and a 1/14 probability is roughly equivalent to the probability of having twins. These results are very different in both literal and probabilistic terms.

Joking aside, this shows the level of aggregation within crypto VC funds. Some VC funds are able to arrange follow-on rounds for their portfolio companies because they also have growth funds. So they will invest in the same company's Seed and Series A rounds. When a VC fund doubles down on its stake in the same company, it usually sends a positive signal to investors participating in later rounds. In other words, the presence of a growth-stage fund within a VC firm can greatly affect the company's chances of success in the following years.

In the long run, crypto venture capital funds will gradually evolve into private equity investments in projects that already have significant revenue.

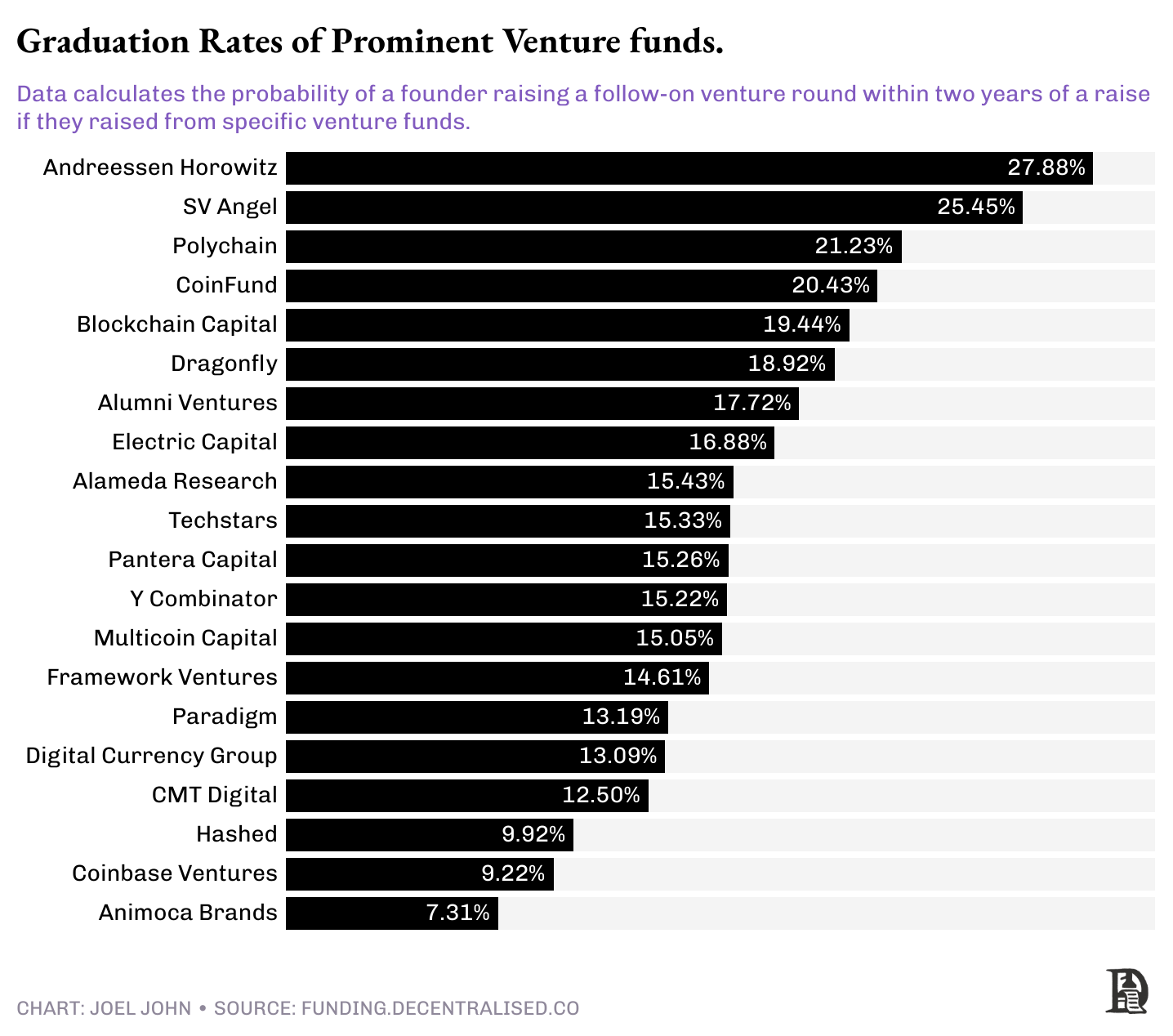

We have a theory for this shift. But what does the data reveal? To investigate, we looked at the number of startups that saw follow-on rounds across our investor base. We then calculated the percentage of companies where the same venture fund participated again in a follow-on round.

That is, if a company received a seed round from A16z, how likely is it that A16z will invest in the Series A round?

A clear pattern quickly emerged. Large funds with more than $1 billion under management tended to participate in follow-on financings more frequently. For example, 44% of the companies in the A16z portfolio received follow-on investments from A16z. Blockchain Capital, DCG, and Polychain followed up on a quarter of the refinancing projects of their investments.

In other words, who you raise money from at the seed or pre-seed stage is much more important than you might think, because these investors tend to back your own projects again.

Customary co-investment

These patterns are in hindsight. They are not meant to imply that companies that raise money from non-top VCs are doomed to fail. The goal of all economic activity is to grow or generate profits. Businesses that achieve either of these goals will see their valuations rise over time. But it does help improve your odds of success. If you can't raise money from this group (the top 20 VCs), one way to improve your odds of success is to tap into their networks. In other words, build connections with these capital hubs.

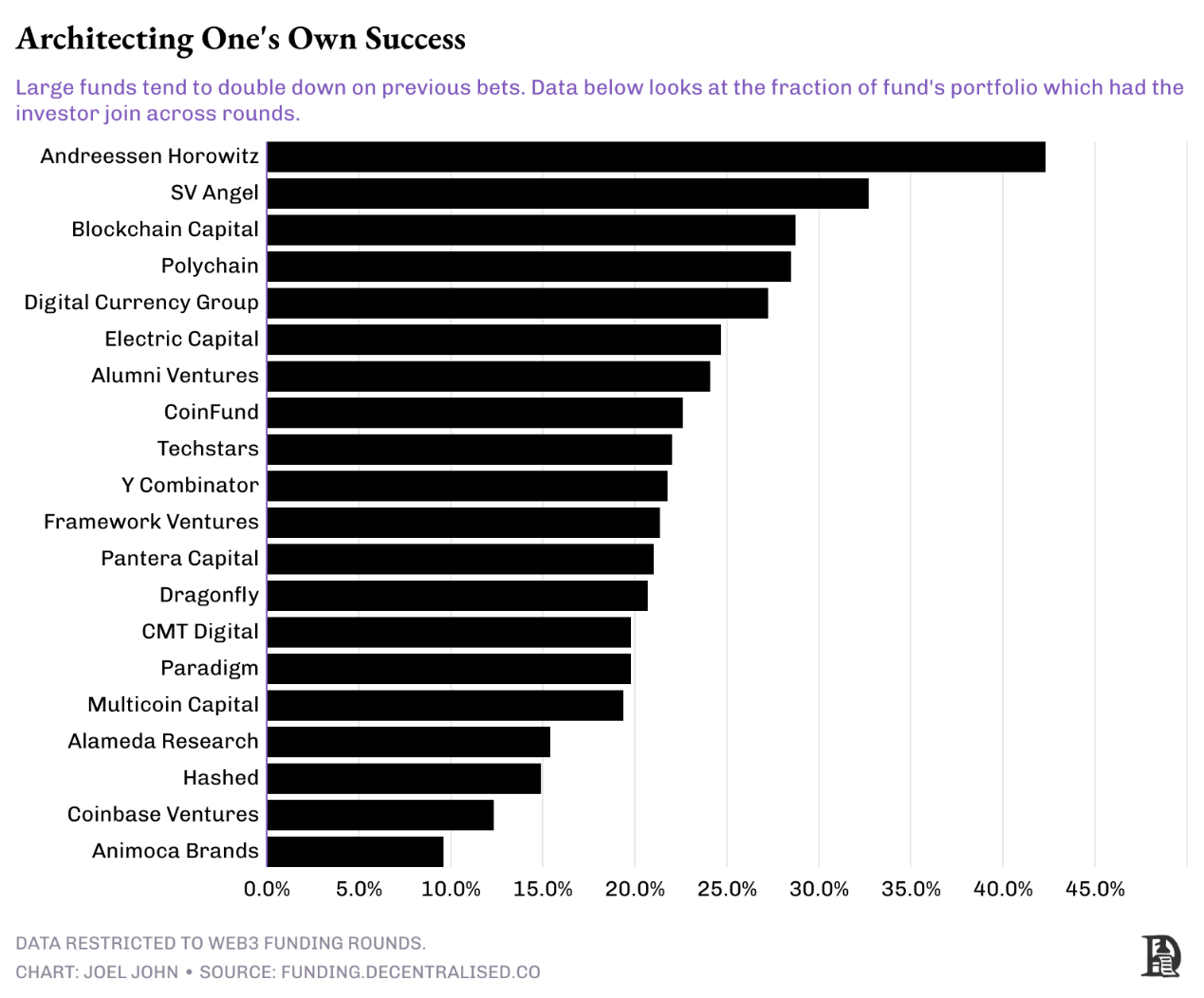

The image below shows the network of all crypto venture capitalists over the past decade. There are 1,000 investors with about 22,000 connections between them. If an investor co-invests with another investor, a connection is formed. This may look crowded, or even feel like too much choice.

However, it covers funds that have collapsed, never returned money or are no longer investing.

The chart below gives a clearer picture of where the market is headed. If you are a founder looking to raise a Series A, there are about 50 funds with investments of more than $2 million. The investor network for these rounds is about 112 funds. And these funds are becoming more concentrated and more inclined to co-invest with specific partners.

The investor groups from which funds can be raised, from Seed to Series A

Funds seem to develop a habit of co-investing over time. That is, a fund that invests in a particular entity often brings in another peer fund, either because of complementary skills (such as technology or to help with marketing) or as a partnership. To examine how these relationships work, this article explores co-investment patterns between funds over the past year.

For example, in the past year:

- Polychain and Nomad Capital have 9 joint investments.

- Bankless has nine co-investments with Robot Ventures.

- Binance and Polychain have 7 joint investments.

- Binance and HackVC have the same number of co-investment projects.

- Likewise, OKX and Animoca have seven joint investments.

- Large funds are becoming increasingly demanding of their co-investors.

- For example, Robot Ventures participated in three of the 10 investments Paradigm made last year.

- DragonFly participated in three rounds of investment with Robot Ventures and Founders Fund, and the three institutions have made a total of 13 investments.

- Similarly, Founders Fund co-invested with Dragonfly three times, accounting for one-third of the latter's nine investments.

In other words, we are transitioning to an era where fewer funds are making large investments and there are fewer and fewer co-investors. And these co-investors tend to be well-known, long-established institutions.

Enter the Matrix

Another way to look at this data is to analyze the behavior of the most active investors. The matrix above considers the funds with the most investments since 2020, and how they relate to each other. You’ll notice that accelerators (like Y Combinator or Outlier Venture) rarely make joint investments with exchanges (like Coinbase Ventures).

On the other hand, exchanges usually have their own preferences. For example, OKX Ventures has a high percentage of joint investments with Animoca Brands. Coinbase Ventures has made over 30 investments with Polychain and 24 investments with Pantera.

Three structural problems can be seen:

- Despite their high investment frequency, accelerators tend to rarely co-invest with exchanges or large funds. This may be due to stage preference. Accelerators tend to invest in early stages, while large funds and exchanges tend to invest in growth stages.

- Large exchanges tend to have a strong preference for growth-stage venture funds. Currently, Pantera and Polychain dominate.

- Exchanges tend to work with local players. Both OKX Ventures and Coinbase show different preferences when choosing co-investment targets. This just highlights the global nature of Web3 capital allocation today.

So if venture funds are clustering, where will the next marginal capital come from? An interesting pattern can be noticed: corporate capital also has its own clusters. For example, Goldman Sachs has co-invested with PayPal Ventures and Kraken twice in its history. Coinbase Ventures has co-invested with Polychain 37 times, Pantera 32 times, and Electric Capital 24 times.

Unlike venture capital, corporate funding pools are usually targeted at growth-stage companies with a solid PMF, so it remains to be seen how this pool will perform at a time when early-stage venture financing is declining.

The evolving network

I started looking into networks of relationships in crypto a few years ago after reading Niall Ferguson’s The Square and the Tower. The book revealed how the spread of ideas, products, and even diseases are linked to networks. It wasn’t until I built the funding dashboard a few weeks ago that I realized it was possible to visualize the network of connections between funding sources in crypto.

Such datasets and the nature of the economic interactions between these entities can be used to design (and execute) mergers and acquisitions and token acquisitions between private entities. Both of these are being explored internally. They can also be used for business development and partnership initiatives. We are still working on how to make these datasets accessible to specific companies.

Let’s get back to the topic.

Can relationship networks really help funds achieve better performance?

The answer is a bit complicated.

The ability of a fund to select the right team and provide sufficient capital will become more important than partnerships with other funds. However, what really matters is the personal relationships that the general partner (GP) has with other co-investors. Investors do not share deals with company logos, but with people. When partners change funds, this connection only transfers to their new fund.

I had a hunch about this, but lacked the means to verify it. Fortunately, a paper came out in 2024 that looked at the performance of the top 100 VC firms over time. In fact, they looked at 38,000 funding rounds for 11,084 companies, and even broke it down to seasonality in the market. The core of their argument can be boiled down to a few facts.

- Past co-investments are not indicative of future collaborations. Funds may choose not to work with other funds if previous investments fail. For example, think of the broken network when FTX collapsed.

- Co-investing tends to increase during periods of mania, when venture capitalists rely more on social signals than due diligence, as funds look to deploy capital more aggressively. During bear markets, when valuations are low, funds deploy cautiously and often go it alone.

- Funds select peers based on complementary skills, so if investors in a funding round all focus on the same area, this can often lead to problems.

As mentioned before, ultimately, co-investing does not happen at the fund level, but at the partner level. In my career, I have seen some people jump between different institutions. Their goal is often to work with the same person regardless of which fund they join. In an era where artificial intelligence is gradually replacing human work, it is helpful to understand that interpersonal relationships are still the foundation of early-stage venture capital.

There is still a lot of work to be done in the study of how crypto VC networks are formed. For example, it would be interesting to study the preferences of liquid hedge funds in capital allocation, or how late-stage deployment evolves with market seasonality. Or how M&A and private equity fit into the mix. The answers may be hidden in the existing data, but these will take time.

Like many other things in life, this will be an ongoing process of discovery and as discoveries are made, relevant information will be communicated in a timely manner.

Related reading: Crypto investment frenzy: Why South Korea has become one of the hottest markets in the world?